“Though it is the hardest thing, to work out one's weight and heft in the world, to whittle down all that I am and give it a value.” - Anna Funder

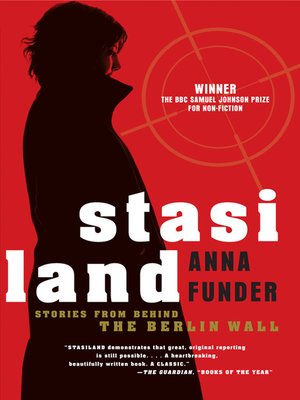

Stasiland is Australian Anna Funder’s literary journalism of Germany’s dark past. In 1996, seven years after the reunification of Germany, Funder is working in television in West Berlin and grows interested in the occupants of the former German Democratic Republic. She explores the stories of the victims and perpetrators of the Stasi in East Germany. Anecdotes are drawn from people who answer to Funder’s newspaper advertisements and Funder’s own acquaintances. Miriam is the ‘tragic hero’ of the text. Funder sympathises with the 16-year-old who came to be considered an enemy of the state. Miriam tells the story of Charlie, her husband that was killed in custody. Miriam’s story is interwoven with the stories of Julia and Frau Paul. Julia is Funder’s land lady, although reluctant about telling her story, shares the details of how her family went through “internal emigration”. Julia was ostracized because of her Italian boyfriend even though she had no intentions to go against the state. Frau Paul shares her story of how her sick baby was taken to West Berlin for treatment and because of her attempts to visit her son she becomes embroiled with a group helping people leave East Berlin. These sad stories are mixed with the stories of the perpetrators, the people who worked with or helped the Nazi, including Herr Winz, Hagen Koch, Karl E. Schnitzler and Herr Bock. Many of these men think back to the GDR with nostalgia and little to none remorse. Funder’s story is a personal and passionate exploration of Germany’s Stasi epoch.

Stasiland is Australian Anna Funder’s literary journalism of Germany’s dark past. In 1996, seven years after the reunification of Germany, Funder is working in television in West Berlin and grows interested in the occupants of the former German Democratic Republic. She explores the stories of the victims and perpetrators of the Stasi in East Germany. Anecdotes are drawn from people who answer to Funder’s newspaper advertisements and Funder’s own acquaintances. Miriam is the ‘tragic hero’ of the text. Funder sympathises with the 16-year-old who came to be considered an enemy of the state. Miriam tells the story of Charlie, her husband that was killed in custody. Miriam’s story is interwoven with the stories of Julia and Frau Paul. Julia is Funder’s land lady, although reluctant about telling her story, shares the details of how her family went through “internal emigration”. Julia was ostracized because of her Italian boyfriend even though she had no intentions to go against the state. Frau Paul shares her story of how her sick baby was taken to West Berlin for treatment and because of her attempts to visit her son she becomes embroiled with a group helping people leave East Berlin. These sad stories are mixed with the stories of the perpetrators, the people who worked with or helped the Nazi, including Herr Winz, Hagen Koch, Karl E. Schnitzler and Herr Bock. Many of these men think back to the GDR with nostalgia and little to none remorse. Funder’s story is a personal and passionate exploration of Germany’s Stasi epoch.

I really enjoyed Stasiland, and I don’t often read non-fiction. Funder’s literary journalism style may not be conventional or the most factual but I found that it is creates a very interesting way to read non-fiction. I could empathise with these real life characters and it added a breath of fresh air into a topic that is now often seen only through the details of school textbooks.

Quick Biography on Funder

Anna Funder was born in 1966 in Australia. She attended school in Melbourne and Paris and studied at the University of Melbourne. Her learning of German at school also led her to study in Germany at the Freie Universitat of Berlin. She studied in West Berlin in the 1980s, while the wall was still up dividing the walls. According to her in Stasiland, during her stay in Berlin, she “wondered long and hard what went on behind that Wall.” (p.4). Before becoming a writer she worked as an international lawyer in human rights, constitutional law and treaty negotiation and worked for the Australian government. In 1989 the Wall in Berlin fell and in 1994 Funder returned to Germany. She visited the Stasi Museum in Liepzig where her guide told her about Miriam Weber. Funder was very curious about Miriam’s story and returns to Berlin in 1996, when Stasiland begins. Funder became a full time author in the late 1990s and worked part time at a television station in West Berlin to fund her research in Berlin. Funder’s context influenced her writing as she grew up in a very democratic and free world, both in Australia and in her visits to democratic Germany. Her views and background as a lawyer in human rights is evident in the narration and direction of Stasiland. While, Funder, attempts to show both sides of the story, Funder is very critical of the ex-Stasi and empathises with the class that was oppressed in the former GDR. Funder stated in an interview she “. . . seems to be very interested in resistance to illegitimate government, or tyranny of any kind. I think that to swim against the stream of popular opinion with only conscience as your guide is risky and brave beyond belief.” It is evident that Stasiland was Funder’s own quest to find the ordinary people who put themselves in risk to fight the Stasi.

Main themes

A few of main ideas in Stasiland include the power of the state and how it was and is questioned. It also questions the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’. These ideas then lead to another main theme of the book which is the exploration of the alienation of people, including women, as the political and social paradigms changed and how they coped and still cope today in a world that was left dehumanized by events in World War II.

The main theme in Stasiland is the power of the state and how it became to be questioned during the late 20th Century. Funder compared the German Democratic Republic and the Stasi to the Catholic Church. The Stasi held such a high power that they were as omnipotent as God and had created their own hierarchy and belief system. It would punish people for lack of belief or even suspected lack of belief. To believe in the state people must have the same “leap of faith” as when decided to have faith in religion. (p. 156-161) Stasi leaders became drunk with power and the motto of the communist leaders was as commented by Erich Mielke, “hang on to power at all costs. Without it you are nothing.” (p.238). However, just as people in the West started to question religion during the period after the bomb, the East Germans began to question and fight against their “religion”. The story of Stasiland revolves around Miriam’s story and her struggle to escape the authority from the young age of 16. Even though Funder writes about both sides, for and against the Stasi, she starts and finishes with Miriam’s story. Most of the other anecdotes found in the novel revolve around similar ideas, such as the story of Frau Paul, who had to go against the authority when asked to help the Stasi capture a West Berliner, even if it meant gaol or not seeing her son. In an SBS interview, Funder admitted to being very “interested in resistance to illegitimate government, or tyranny of any kind”, it then follows that her first book would follow the idea of the brave act of resistance against oppressing authoritarian figures.

The main theme in Stasiland is the power of the state and how it became to be questioned during the late 20th Century. Funder compared the German Democratic Republic and the Stasi to the Catholic Church. The Stasi held such a high power that they were as omnipotent as God and had created their own hierarchy and belief system. It would punish people for lack of belief or even suspected lack of belief. To believe in the state people must have the same “leap of faith” as when decided to have faith in religion. (p. 156-161) Stasi leaders became drunk with power and the motto of the communist leaders was as commented by Erich Mielke, “hang on to power at all costs. Without it you are nothing.” (p.238). However, just as people in the West started to question religion during the period after the bomb, the East Germans began to question and fight against their “religion”. The story of Stasiland revolves around Miriam’s story and her struggle to escape the authority from the young age of 16. Even though Funder writes about both sides, for and against the Stasi, she starts and finishes with Miriam’s story. Most of the other anecdotes found in the novel revolve around similar ideas, such as the story of Frau Paul, who had to go against the authority when asked to help the Stasi capture a West Berliner, even if it meant gaol or not seeing her son. In an SBS interview, Funder admitted to being very “interested in resistance to illegitimate government, or tyranny of any kind”, it then follows that her first book would follow the idea of the brave act of resistance against oppressing authoritarian figures.

Stasiland illustrate that nothing is simply black and white, good or bad. The after the bomb period was characterised by a questioning of morality. The Allies had ‘won’ in the name of freedom and democracy but they had also killed at least 129,000 Japanese with the dropping of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Humans had created a bomb so powerful that it could destroy the planet; this led to a questioning of morals and beliefs in people. While Funder wrote this book in the late 1990s, after the post-WWII period, Stasiland, questions morality. Stasiland demonstrat

Due to the political and social changes in Eastern Germany during and after the GDR changed, many people were left alienated. The Berlin Wall in Stasiland is depicted as a physical and symbolic representation of the power that the GDR held over its people and how even now that it has been destroyed many people were “defined by the physical and psychological restraints of the wall” (p. 234) During the GDR many people withdrew into ‘internal emigration’, sheltering their inner lives from the state. Stasiland explores, as its subtitle suggests, the “true stories of people behind the wall”, it is the story of the oppressed and what life is currently like for ex-East Germans occupants. As the character of Julia said, they were aware of what “could be said outside the home (very little) and what could be discussed in it (most things)” (p.95) However, as the Stasi read and heard even the most personal of home conversations and could punish people even for being suspects of blasphemy, people began to learn to keep to themselves and live within them. Funder chooses mostly women to tell their stories, this creates a sense that it was the women who were the most alienated and oppressed during the GDR. The ex-Stasi, the authority figures, were all male. When Funder visits the Stasi HQ in Berlin she is told there it only had toilets for men. There were many men who were victims of the Stasi regime, however, Funder does not focus on them. Also, Funder’s experience with the swimming pool becomes a symbol of the over-regulation and absurdity of the control that the GDR imposed. In Chapter 14, Funder had trouble following the rules of a swimming pool and felt quite out of place. This then becomes symbolic of the former GDR and how people would have felt living in a place that was so constrained by unfair rules.

Due to the political and social changes in Eastern Germany during and after the GDR changed, many people were left alienated. The Berlin Wall in Stasiland is depicted as a physical and symbolic representation of the power that the GDR held over its people and how even now that it has been destroyed many people were “defined by the physical and psychological restraints of the wall” (p. 234) During the GDR many people withdrew into ‘internal emigration’, sheltering their inner lives from the state. Stasiland explores, as its subtitle suggests, the “true stories of people behind the wall”, it is the story of the oppressed and what life is currently like for ex-East Germans occupants. As the character of Julia said, they were aware of what “could be said outside the home (very little) and what could be discussed in it (most things)” (p.95) However, as the Stasi read and heard even the most personal of home conversations and could punish people even for being suspects of blasphemy, people began to learn to keep to themselves and live within them. Funder chooses mostly women to tell their stories, this creates a sense that it was the women who were the most alienated and oppressed during the GDR. The ex-Stasi, the authority figures, were all male. When Funder visits the Stasi HQ in Berlin she is told there it only had toilets for men. There were many men who were victims of the Stasi regime, however, Funder does not focus on them. Also, Funder’s experience with the swimming pool becomes a symbol of the over-regulation and absurdity of the control that the GDR imposed. In Chapter 14, Funder had trouble following the rules of a swimming pool and felt quite out of place. This then becomes symbolic of the former GDR and how people would have felt living in a place that was so constrained by unfair rules.

Anyone interested in the GDR should read this book; it has some very interesting stories. Facts, can really be, better than fiction.

No comments:

Post a Comment